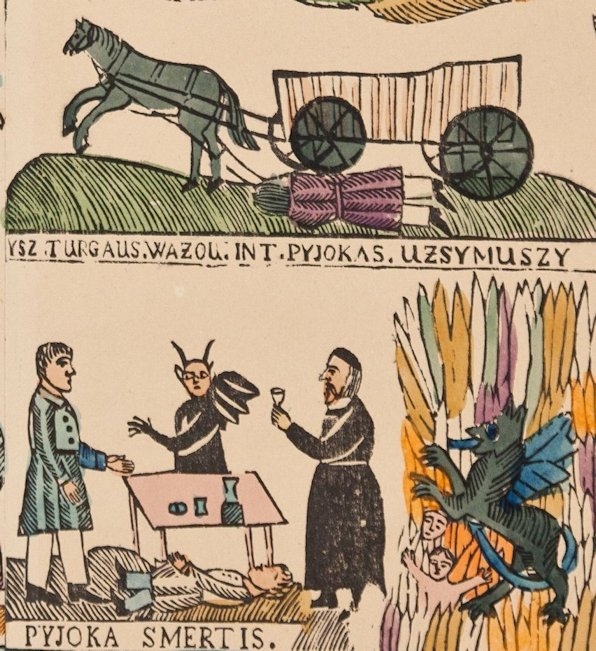

A warning at carnival time

He is undeterred by the sight of his companion lying in a drunken stupor under the table. And he cannot see, of course, the chasm of hell shown in the next scene, behind the innkeeper’s back, so he cannot heed the souls of other sops before him, gesticulating desperately from their seat of penance amid tongues of flame, guarded by a horrifying demonic figure. Neither does he know that he, too, will doubtless shortly share the fate of those penitents, when his earthly life is tragically cut short under the wheels of a cart.

These three terrifying scenes are details from a woodcut from Samogitia, printed from four blocks dated to the mid-19th century (see database no. Gr.Pol.2391/60 MNW). They were executed at a time when various organisations were mounting an organised battle against the plague of alcoholism among the peasant classes. The sobriety movement, founded around 1825 in Protestant circles in the USA, spread rapidly to Europe. Most of the first temperance societies were set up by the Church. In 1844 Fr Alojzy Ficek established the Sobriety Fraternity in Upper Silesia, and this was emulated in many dioceses as far afield as Samogitia, where the founder and mentor of the temperance movement was Fr Maciej Wołonczewski (Valančius), bishop of Samogitia in the years 1849-1875. It was on his initiative that many religious and moralising books and pamphlets aimed at the peasant classes were printed at this time, with the purpose not only of moulding religious attitudes but also of tackling the weaknesses of the faithful. It was probably the bishop who commissioned one of the region’s German printing houses to make the lithographs that later became the models for this set of four woodcut blocks used to produce this print depicting the tragic death of the drunkard contrasted with the dignified dying of the abstinent. The matrices were made by a Lithuanian woodcarver and vendor of religious paraphernalia from Darbenai, Aleksandras Vinkus. The scene, which is virtually identical with the original lithograph, but supplemented with inscriptions in the Samogitian dialect, must have been popular among the peasants, for the carver made analogous sets of blocks on two occasions.

Today we do not know to what extent these popular images influenced the decision to take the oath of sobriety. They probably helped some people to keep their resolve or the promise forced on them by their environment. The prospect of inevitable, eternal punishment in the form of hellfire must surely have helped on occasion to quell the longing for another rowdy night out at the tavern.

Beata Skoczeń-Marchewka